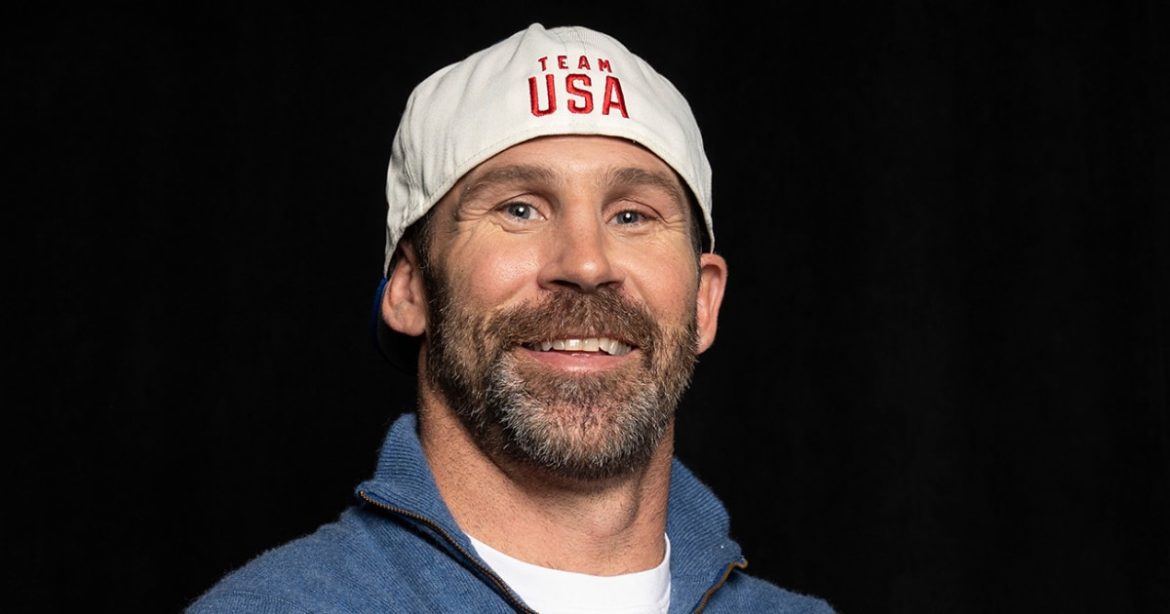

When the topic of his age comes up, Nick Baumgartner smiles. He knows the questions are coming. For the past four years, it’s all anyone wants to talk to him about.

Baumgartner, a Michigan native, enters the Milan Cortina Olympics as one of the world’s best at snowboard cross, an event where competitors jostle for position over a series of banked turns, speed bump-like hills and jumps, all trying to reach the finish line the fastest. Four years ago, Baumgartner won an Olympic gold medal in mixed snowboard cross with U.S. teammate Lindsey Jacobellis.

But the fascination with Baumgartner isn’t just about his talent. It’s about how he’s maintained it at an age that’s considered, by the standards of snowboarding, ancient.

When he won gold four years ago in Beijing, he was 40. Next month in Italy, while competing at his fifth Olympics, Baumgartner is trying to do it again at 44.

He’s old enough to have a son who has graduated from college and a spot on the U.S. national team for 21 years — longer than two of his U.S. Olympic teammates, 17-year-olds Ollie Martin and Alessandro Barbieri, have been alive. In Italy, he will be the oldest U.S. male snowboarder by 14 years.

“I’m in a sport against children,” Baumgartner said. “Snowboarding is dominated by youth, and to have a guy like me, the elder statesman, I love it, man. It makes me proud.”

It also makes Baumgartner part of a trend. Advancements in training and recovery have made it more common for older athletes to hold their own at ages that once would have been associated with retirement. Tom Brady won a Super Bowl at 43 in 2020. This NFL season’s MVP could be 37-year-old quarterback Matthew Stafford. LeBron James turned 40 last season, then earned second-team all-NBA honors, effectively making him still one of the league’s 10 best players. At these Olympics, some of the most high-profile athletes on Team USA are its oldest, including 41-year-old skier Lindsey Vonn and 36-year-old hockey star Hilary Knight.

“I’ve been in this game for 21 years, and I’m still the underdog, even after a medal,” Baumgartner said. “Because now I’m older, so everyone’s counting me out, and I love it. Fall asleep on me and tell me I can’t, and we’ll show that we can.”

The focus on the 44-year-old Baumgartner’s age, and questions of whether it could prevent him from keeping up with younger competitors in Milan Cortina, is amusing to Josh Baumgartner, the second-oldest of five Baumgartner siblings. Keeping up in competition despite a significant age difference is all Nick has ever known, he said.

Nick grew up in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, just outside the 3,000-person town of Iron River, as the youngest of four brothers, with a sister just one year behind, and he enjoyed “a different kind of childhood than most people experience,” his brother said. The brothers were each two years apart in age, but younger siblings were never babied; Nick recalled being on the receiving end of numerous pummelings by his older brothers.

“You want to win? You earned it,” Josh said.

The siblings operated under a loose set of rules. They had to be home by dark to check in, but didn’t have to stay home. If the kids’ adventures were going to require crossing the local highway, U.S. 2, to get to favorite hangout spots like Sunset Lake, the parents wanted to know. But otherwise, the kids were free to roam around Iron River, playing football in their front yard and basketball on the playground, or cutting through woods and swamps.

“We had our boundaries of where we could go, but it covered miles,” Josh said. “Surprising we all survived it, to tell you the truth.”

When Josh was 10, he said, he got a snowboard for Christmas, and he recalled that, soon, his brothers wanted to snowboard, too. Nick became so good that he left the football team at Northern Michigan University to become a pro snowboarder. At the same time, in 2004, Baumgartner became a father to a son, Landon. Nick made the Olympics in 2010, 2014 and 2018 but left each Games without a medal. Each missed opportunity left Baumgartner wondering how many more chances he might have.

It wasn’t for lack of trying.

Baumgartner likes to say he will outwork any other racer, and his brother suggests that isn’t hyperbole. To fund the expenses of professional snowboarding, Baumgartner spent his summers working for a Wisconsin-based concrete company, where he poured patios, sidewalks and driveways. In 2021, weeks before the Beijing Olympics, Baumgartner got a call from Josh, who is a contractor in Aspen, Colorado, asking whether he would come to Colorado to help pour vertical walls. For eight hours, Nick pulled multiple walls’ worth of concrete by shovel. A 10-foot section of a 6-inch concrete hose can weigh around 400 pounds, Josh said; that night, they were constantly maneuvering about 80 feet of hose, up and over walls.

“It was the craziest day of work ever in either one of our lives,” Josh said. The job finished at midnight. By morning, Nick had left for snowboard camp.

He could bounce back quickly from hours spent hunched over while pouring and leveling concrete when he was younger, but by Baumgartner’s late 30s, the recovery might take weeks.

If the concrete work didn’t make it easier to take care of his body, neither did his training arrangements. The gym where he has long trained is in Marquette, Michigan, nearly 90 miles from his home. To reduce the commute, Baumgartner began working out at the gym on Mondays, staying the night in his van and working out again the following day before driving back to Iron River. He repeated the commute on Thursdays.

All of that was why Baumgartner described “heartbreak” in an emotional postrace interview at the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing when he failed to medal in individual snowboard cross.

“I’m 40 years old,” Baumgartner said. “I’m running out of chances.”

Days later, his life changed when he and Jacobellis combined to win gold. He left China and flew into Green Bay, Wisconsin, a 140-mile drive from Iron River. Halfway to his hometown, locals who had advance warning of his arrival began gathering along the road, cheering Baumgartner as he passed. As the car got closer to home, Baumgartner’s son gleefully recorded his father tearing up seeing more and more spectators line the road.

“Craziest thing I’ve ever experienced,” Baumgartner said. “I’m still not that famous. You get about three hours away from my home, it’s gone. But at the grocery store in Iron River? Most famous guy!”

When the celebrations died down, Baumgartner had to figure out how to maintain his advantage over his competitors for four more years. As a young professional, Baumgartner thought of himself as more of a football player than a snowboarder, and his training reflected it. In the weight room, he would focus on adding muscle to his chest, triceps and biceps on some days, and his legs and back on others, instead of exercises targeted at the demands of snowboarding.

Broad-shouldered and thick-necked, with a mustache and a five-o’clock shadow, Baumgartner still looks like a football player. But he’s no longer training like one. The boost in funding from sponsors and other sources, like writing a memoir, that Baumgartner received after winning gold in Beijing reduced his reliance on side jobs. With more time and less wear and tear, he found “way more efficient ways to do what I do, so that I’m not wasting time, energy or power doing something that’s not going to correlate directly to my sport,” Baumgartner said.

He developed one very efficient way to train this winter, just steps from his front door, by building a snowboard cross course encircling his home. He drops in from a platform of hardened snow and ice, carves banked corners and pumps his legs to get through a series of “rollers” hills, and whips around to the finish.

His training targets the same fast-twitch muscles that propel sprinters, “all working on that explosiveness to try to be fast out of the gate and have that power,” he said. At his gym in Marquette, he sprints while pulling a weighted sled, then does box jumps. He’ll still do squats and bench-press as in his youth, but now he does them while monitoring a gauge that can tell him the speed with which he is pressing the bar; a reading slower than 0.6 meters per second tells him something is wrong and that he might be overly tired. To recover, Baumgartner will use a sauna, often five days a week.

“[In a] gravity-friction sport, mass tends to win, right?” he said. “So you just have to be able to get that moving. I always tell people, this bus will go fast downhill, but I got to get it out of the garage fast enough. So as long as I can keep that speed and stay in the hunt, I don’t care if I’m … behind. I’m still in the hunt.”

And he has remained on the medal hunt because his years of falling short at the Olympics forced him to become patient, he said.

“I’ve seen so many kids that have all the talent in the world to beat me, and on paper, they should crush me,” he said. “And they never beat me, and it’s because I put in the miles.”

“I’ll see kids that I think are going to win, and it takes them six years to win, and some people quit before that happens. And I try to tell them, just stick with it. Stick with it. It’s coming. It’s coming. But it’s so frustrating for some people to work through that.”

Baumgartner understands he can’t compete at his current level forever. He’s already thought about what he will do once snowboarding ends: motivational speaking. But he also knows the Winter Olympics return to the U.S. in 2034, in Salt Lake City. Can he snowboard into his 50s?

He smiles again. He has considered the possibility.

“In my mind, it should be the best story of the Olympics,” his brother Josh said. “The old guy you shouldn’t count out.”

#Nick #Baumgartner #44yearold #Olympic #snowboarder #guy #shouldnt #count1769774404