He described running for governor as slower in some respects — and much more tactile and personal, with the national noise he once reveled in less relevant to his goals these days. Ramaswamy has visited each of Ohio’s 88 counties, replicating an aggressive strategy he deployed in Iowa as a presidential candidate and delighting local Republicans who worried that he would try to coast on his newfound celebrity while skipping their chicken dinners.

“It was important to me, in part, because I wanted to make sure we listened,” Ramaswamy said. “There’s no substitute for actual real world interaction. The echo chambers of the internet are not sufficient — in fact, not only not sufficient, maybe outright misleading in terms of what’s actually on real voters’ minds.”

Ramaswamy’s staff still posts for him on X and on Instagram. But he deleted the apps from his phone at the beginning of the year, citing among other distractions the racial slurs that clutter his mentions. He said he appreciates the extra time he now has for exercise and family. He and his wife, Apoorva Ramaswamy, a surgeon, are expecting their third child next month.

If Ramaswamy’s Trumpier-than-Trump bid for president reflected his vision of the GOP then, as well as what he believed he could contribute to it, his different calibration for 2026 hints both at where he sees the party going and and how he sees himself at its center. His approach this time also suggests an understanding that, given his lock on the Trump endorsement and front-runner status in the primary, his time is better spent appealing to mainstream voters who are more impressed by maturity and competence than by hot takes and right-wing soundbites.

Whether Ramaswamy’s rebrand is sincere or cynical is something Ohio voters will decide. Early polls show a general election that is up for grabs. But Republicans enjoy profound structural advantages in a state where they very rarely lose statewide elections. Vice President JD Vance, a former senator from the state, has loaned his top political advisers to Ramaswamy, an old law school friend.

Democrats backing Amy Acton for governor have characterized Ramaswamy as a flaky tech bro campaigning from a private jet. Acton, a physician, served as DeWine’s health director during the early months of the Covid pandemic and often talks of growing up poor in Youngstown.

Ramaswamy “will continue more of the same policies that have made life unaffordable for working Ohioans,” said Katie Seewer, a spokesperson for the Ohio Democratic Party. “It’s no surprise that he’s desperately trying to rebrand from the image he built his political career on.”

There is also right-wing skepticism brewing in the social media world Ramaswamy left behind. Casey Putsch, a political novice known for his “car guy” videos on YouTube, last month launched a primary challenge that, so far, exists mostly on X. Putsch constantly trolls Ramaswamy there, having gone so far as to call him an “Indian Anchor baby.”

Putsch defended his use of the derogatory term, which is meant to undermine citizenship guaranteed to U.S.-born children of immigrants by the 14th Amendment. He said he has been encouraged by an anti-Ramaswamy “roar on social media” that he described as “deafening.”

“There’s nothing about this man,” Putsch said, “that’s Ohio.”

‘Grounded’ campaign, sharpened ‘perspective’

Ramaswamy grew up in Cincinnati, where his mother and father settled after emigrating from India. He has emphasized how he attended diverse public schools through eighth grade. A scuffle with a classmate prompted his parents to enroll him in a private Jesuit high school, where he was the only Hindu student, he wrote In “Woke, Inc.,” the 2021 book in which he railed against business practices that prioritize social justice and environmental issues.

An Ivy League education and work at a hedge fund followed. By the time he was 30, he had led what was then the largest initial public offering in biotech industry history. The company’s Alzheimer’s disease treatment would fail, but not before extending a financial runway for the political ambitions Ramaswamy had upon returning to Ohio in 2019.

“My call to serve the state was to give every other kid in the state the same American dream that I had lived,” Ramaswamy told the workers at his event last week. “We’re raising our kids in circumstances that our families would have never imagined 30, 40 years ago. And the extraordinary part of that story is that it’s really not that extraordinary in the United States of America.”

The Cleveland-area event, which drew local laborers, including members of a carpenters union that endorsed his campaign, was an example of the type of small-scale, “real world” campaigning Ramaswamy has emphasized in his campaign for governor. He grabbed arms and elbows and gently slapped backs as he worked the room, stopping at one point to snag a cookie from a deli spread. After delivering an abbreviated version of his usual speech, in which he promised to make Ohio more attractive and predictable for businesses by lowering property taxes and phasing out the state’s income tax, he took questions.

“What’s your perspective on that?” Ramaswamy replied more than once — a trick that allowed him to learn more about unfamiliar subjects, like plumbers’ licenses, without coming across as ignorant or uninterested.

“He’s one of the most impressive candidates I’ve run into at any level,” said Tony Schroeder, secretary of the Ohio Republican Party and chair of the Putnam County GOP. “He’s real inquisitive, a very intriguing guy.”

Ramaswamy said his most meaningful conversation with a voter came last April at a Lincoln-Reagan Dinner for Republicans in Wayne County. As he engaged a group of protesters outside, an Army veteran complained about the recent firings of federal employees — a result of cost-cutting programs that Ramaswamy and fellow billionaire Elon Musk had helped establish for Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency. Ramaswamy refocused the exchange around an issue he would have more control over as governor: ensuring that veterans’ benefits aren’t disrupted. He then invited the woman to be his guest at the dinner. During his speech, he asked her to join him on stage.

“I appreciate you giving us a chance to talk to you outside. I really wasn’t expecting it, because I’m not a Trump person,” the woman is seen telling Ramaswamy in a video that his campaign posted on social media. “It’s given me a different perspective talking to you.”

Ramaswamy said such experiences have sharpened his perspective, too.

“I think it’s been a year where running this as a true, real world campaign, rather than the way other campaigns may more traditionally be run, has grounded me in what’s important,” he said. “I’m hopeful that’s going to make me not only a better candidate this year, but a better leader for our state.”

Wanted: A ‘strong Christian’

In some ways, the “real world” Ramaswamy of 2026 is a response to the ugliness that has bubbled around him since he entered politics.

His race and religion were constant subjects of curiosity during his presidential bid. Iowa voters peppered Ramaswamy with so many questions about his Hindu faith that he began tossing out Bible verses to demonstrate a fluency in Christianity. The episodes — mostly polite, if awkward — foreshadowed hostilities that have erupted more recently.

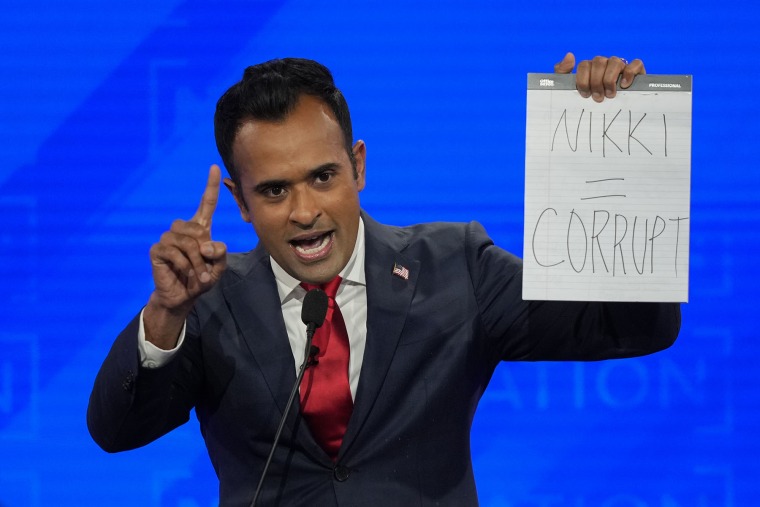

Ramaswamy emerged as a surprisingly tough — and, to many of his rivals, annoying — White House contender. He threw partisan red meat with abandon and youthful swagger. Along with his pitch to end birthright citizenship was a proposal to strip voting rights from 18- to 24-year-olds unless they had passed a civics test. Both ideas run afoul of the Constitution.

Then, a moment between Ramaswamy’s two campaigns showed subtle signs of a political identity in transition. Some on the right have not forgiven him for his December 2024 defense of H-1B visas for high-skilled tech workers — a missive memorable in part for invoking stereotypically nerdy 1990s sitcom characters such as Screech and Steve Urkel.

By most metrics, Ramaswamy’s campaign for governor is off to a strong start. He has already raised $20 million, a historic sum that does not include what is expected to be a considerable investment from the wealthy candidate. He has siphoned union support away from Democrats. Potentially credible primary challengers with statewide name recognition dropped out of the race or decided not to run at all.

But questions about Ramaswamy’s religion came hurtling back as he homed in on a choice for lieutenant governor — a dynamic that even his supporters candidly acknowledge. In his debut as Ramaswamy’s running mate at an event this month in Cleveland, state Senate President Rob McColley and other speakers repeatedly emphasized McColley’s Christianity.

“Vivek and I are of different faiths, but he understands how important Christians are to the future of Ohio,” Aaron Baer, the president of the Center for Christian Virtue, an influential lobbying group in the state, said in introductory remarks. “Vivek made a commitment to me that when he was going to choose his lieutenant governor, he was going to pick a strong Christian.”

Ramaswamy confirmed having such conversations with Baer and pastors across the state but characterized his commitment as something less than a promise. One of the runners-up to McColley was former state Treasurer Josh Mandel, who is Jewish but has close ties with evangelical Christian groups.

“A couple of them asked me, ‘Would you be open to choosing a Christian conservative for lieutenant governor?’” Ramaswamy said. “And I gave them my commitment that, absolutely, I was open to that.”

The quiet part out loud

There also are hushed conversations about how, in its 223 years of statehood, Ohio has exclusively elected white men as governor. Only once since 1990 has a Republican not won the governorship: in 2006, when the party nominated a Black man for the job. Ken Blackwell, at the time Ohio’s sitting secretary of state, lost in a landslide that year, part of a nightmarish national election for the GOP.

Some opposed to Ramaswamy have been saying — or posting — the quiet part out loud. And it has gotten inside Ramaswamy’s head. In a New York Times guest column last month that warned of rising antisemitism and racism in the Republican Party, he wrote about “calls to deport me ‘back to India’” in his social media feeds.

#Vivek #Ramaswamys #campaign #Ohio #governor #returned #real #world1769164033